Body's law

Who are they, these characters who stand out less than they seem to extract themselves, temporarily, from a foggy, heavy, enveloping substance - sticky like clay, floating like the clouds padding distant star clusters? Who are these characters watching us?

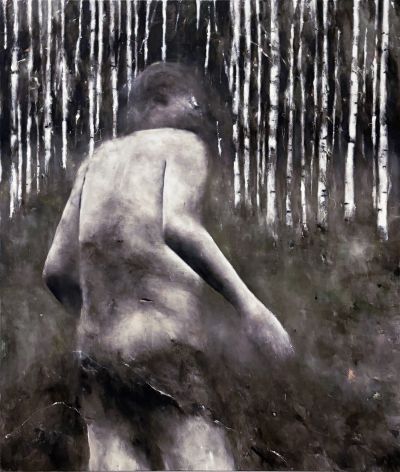

A poorly posed question, with approximate terms. No “who”, no “they”, even less “characters” in Frantz Metzger's paintings. Just “figures”. And their indistinct faces, eclipsed or eaten by who knows what leprous fog, removed from the laborious demands of expressive and physiognomic exactitude, are certainly not “looking” at us. Frantz Metzger draws titles and stimuli from Dante, Hölderlin and Pascal. At the same time, however, and without paradox, Metzger's painting is fiercely anti-literary: he makes no pretensions to the “psychology of characters, these living beings without entrails” (Valéry).

The fine craftsmanship that went into shaping these bodies, these volumes obtained through the skilful, colorist grace of the infinite modulation of grays (the science of dosing and shifting light-whites and brown opacities) - this fine craftsmanship never rings hollow. Otherwise, Zoran Music, Baselitz, even Bacon (who played no small part in shaping Frantz Metzger's temperament as a painter) would be empty. That doesn't sound hollow - it sounds full. What fills these literally disfigured bodies?

Let's take a look at the works on paper: kneading of silhouettes, irregular kneading of contours (Schiele is undoubtedly not far off), squirts, splashes, effusions. It's suffering: aching flesh. Back to the painting: Crucified's lividity, the body's vessel in the process of dissolving. Grey-white, semi-solid masses of flesh, of which we might well say what Fritz Zorn wrote, with his appalling lucidity, of his cancer: “It was as if all the tears I hadn't been able - and hadn't wanted - to shed in my life had gathered in my neck to form this tumour”. But there are these couples too. Jouissance, supplice, what's the difference, not just because one, as we've been told often enough, is the flip side of the other - but because this painting is purely corporeal, purely sensorial. And that the location of the cursor (agony or orgasm) matters less than the sensitive alterations of the affected subject. The way his flesh dissolves, melts, or radiates and persists.

In any case, these bodies only half belong to themselves. They get stuck, entangled in the depths. They sometimes hesitate on the “edge” (Frantz Metzger likes the word and the idea) of animal life. As if badly awakened from the sleep of consciousness proper to primordial existence. But Metzger is less interested in primordial existence for its own sake than in the regressions and mutations it determines. For the impulses and thrusts that bring us back to it or pull us out of it. For the “forces that work reality” (Artaud). And maintain its permanent motion, its moving inconstancy. The body is, as we understand from this work, the best witness to this.

- Damien Aubel, journalist and art critic