PÉNINSULES

from the Iberian to the Armorican Peninsula

Cedric Le Corf

Loo & Lou Gallery - Haut Marais

16.09 - 29.10.2020

There are artists who have a brutal inertia and others who are reclusively inclined, both symmetrical ways of separating art from life. This great modernist separation remains significantly followed. Separating oneself from the world and its breath, its increasing fragility, was never something Cedric Le Corf consented to. He does not practice detachment or indifference, and refuses to break with the natural order. The order itself, not merely its depiction: an order that is hard to define, irreducible to our reason, and all the more necessary to excavate from within, through the irrepressible energy of the shapes.

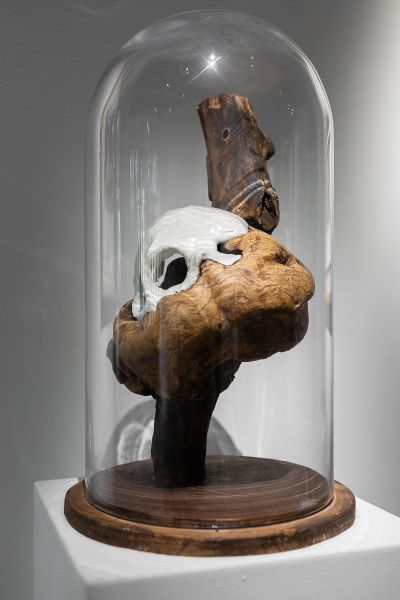

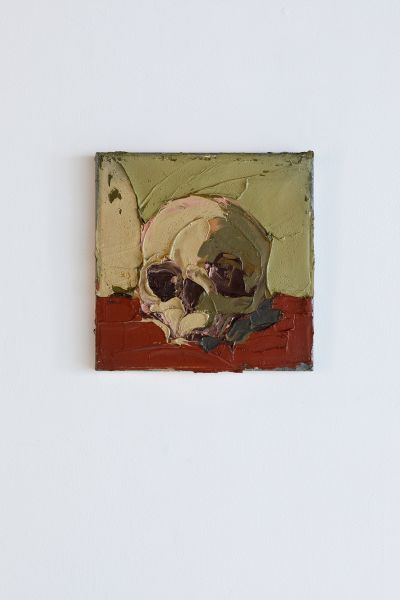

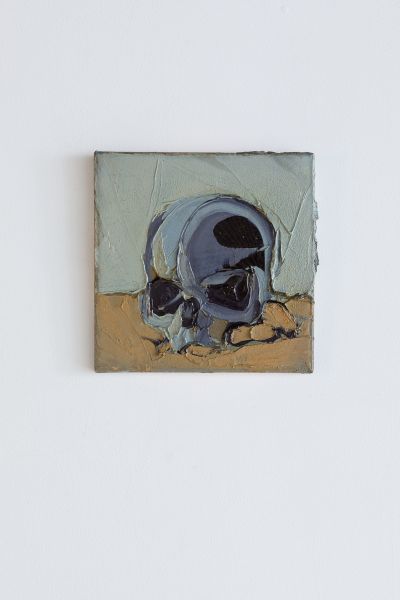

More than figurative, Cedric Le Corf’s sculptures, prints, and drawings consequently capture the heart, perhaps sacredly, through organic mystery in which we are merely the ephemeral passengers. What is it made of, this world, his world, which he himself calls baroque, out of expressionist choice and active listening of its elements, in which he seeks his proper place? The anatomy, both human and animal, seems to be the key player, and almost the implacable law from which derive all kinds of bones: skulls, jaws, limbs, fragments... If it were not for the fact that Le Corf employs materials, from wood to porcelain, which immediately restore the truth of his approach, one might say of Le Corf that he strips more than he sculpts.

His darkest works, which evoke Gericault and Delacroix (although there’s no banal mimicry), contain a tender, active, rough humour, which is not the effect of overly clever contrasts. Rather there is a suggestion, since there is an element of the baroque, of a sense of the circulations and mutations at the heart of which the vital forces victoriously confront the powers of suffering, doubt and death. It’s no secret that Le Corf’s curiosity has always taken him in the direction of those humanists most determined to understand the machinery of bodies and fluids responsible for such a miraculous operation. Michael Servetis, a martyr for truth, and Andreas Vesalius sit in his imaginary pantheon, as do the somewhat closer Philippe Etienne Lafosse, Jacques Fabien Gautier d’Agoty and Honore Fragonard, cousin to the famous painter. In the ancient world, anatomy and dissection were one and the same: there was no alternative to opening up the body in order to understand. But what of art, where the “open form” often remains an excuse for works empty of any meaning. I like Le Corf’s response and his way of naturally reconnecting with the great Sevillians, from Montañés to the young Velazquez (beyond the Romantics and Baselitz). For them, depiction was suddenly threatened by its very realism, figuration by disfiguration. The boundaries gently fall away and, as Le Corf might say, bodies become landscapes. In blurring the kingdoms, anatomy comes to life and enchants us.

— Stéphane Guégan

Scientific advisor to the Presidency of the Musée d'Orsay and the Musée de l'Orangerie

Hölderlin called it the "journey to the colony". In order to find our origins, we must abandon them, forget them. Victor Ségalen, after exploring the Middle East and the Pacific, returned to Brittany. My journey is also marked by "steles".

Imbued with a Rhenish heritage, from Dürer to Grünewald, and schools of polychrome wood, I penetrated the marine ode in my studio on the island of Groix, in Berlin, the laceration of German expressionism, then, in residence at the Academy of Fine Arts at the Villa des Pinsons in Chars, the landscapes' tranquility of the Vexin painted by Corot. Then, as a member of the Casa Velázquez in Madrid, I discovered Spanish baroque and its worship of death, its sculptures painted with waxy flesh or enameled ceramics by Juan de Juni and Alonso Berruguete. And finally, the eternal return to the Celtic land where by a happy coincidence in the meandering Scorff Valley's landscape, only a few steps away from the enclosures, the porz a maro (the gates of death), the famous dance of death of Kernascléden, and the marvelous rood screen of St Fiacre, I put my bag down and opened my workshops, an imaginary museum in the colors of the "Sarrazin". A return to the source can only be accomplished if a poet sings, I had to take this detour, the foreign road to start over again without end.

— Cedric Le Corf

Losing the daily Midi; crossing courtyards, arches,

bridges; try the branched paths; run out of breath at the steps, ramps, climbing ;

Avoid the precise stele; go around the usual walls; stumble

ingenuously among these fake rocks; jump this ravine ;

to linger in this garden; to go back sometimes,

And by a reversible lace finally mislead the quadruple sense of the Points of Heaven.

— Victor Ségalen - Steles