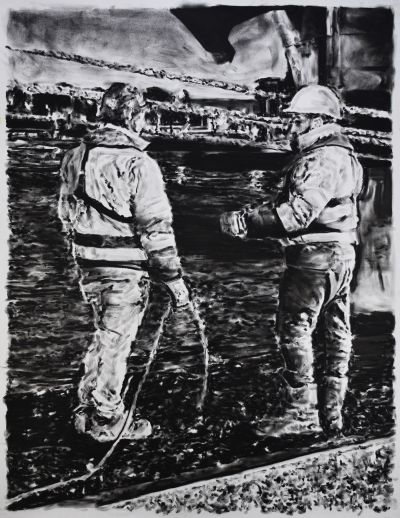

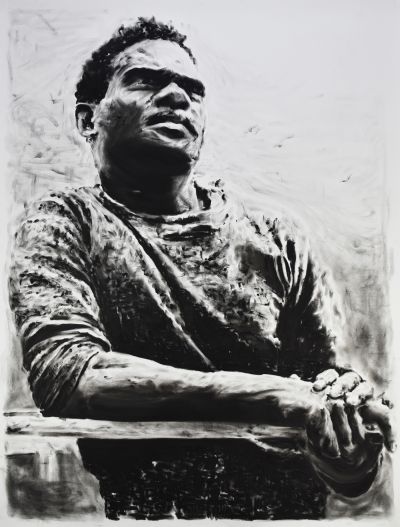

“It's 2 a.m. and freezing cold. It's snowing. A ship is slowly approaching the quay to dock safely. We hear the sound of the VHF marine radio, the roar of the wind, the bow thruster.” Joren Van Acker sets the scene. Our senses are awakened, and the artist literally draws us into his world. This story could be the opening of a crime novel or the first frame of a detective film. We see it. We're there. Drama is just around the corner. It's true that the Belgian artist's drawings contain a cinematic dimension, whether in the framing, the tension of a scene or the light, to the point of referring to Expressionist cinema, so sharp are the contrasts between the blacks and whites of his charcoal drawings. And yet, nothing is romanticized. Everything Joren Van Acker describes is his daily life, what he sees, his world as a maritime worker in Ghent. No fiction, fantasy or exoticism. No dock of Medamothi, the island of nowhere where Rabelais landed Pantagruel and Panurge on their way to the Dive Bacbuc oracle. Joren Van Acker is a docker himself, and he doesn't give up. There's no question of giving up, as it provides him with vital energy and infuses his imagination. “It's a world I can't leave. By nature, I'm also a 'worker'. It keeps me “honest”. It nourishes me enormously as a person and keeps me grounded in life. I'm convinced that an artist always needs to stay grounded in reality.”

A ship in shadow, a sailor gazing at the horizon from the ship's rail, others preparing the ship's gangway for departure or pulling a cable to tie up to a tug... In some fifteen drawings created for the Lou&Lou gallery, Joren Van Acker presents anonymous people, each embodying an aspect of the maritime world as a whole. He puts the spotlight on workers who are generally invisible. Hence the title of the exhibition, “Embodied Forgotten Places”. “I could phrase this title another way, 'a world that remains hidden from others' because most people don't even suspect its existence. Let's not forget the working class, the aircrew, the people on the front lines in all weathers, day and night.” Surprisingly perhaps, there's no political discourse or social criticism - he refuses to do so. Or else, in the background, without a claim being raised like a banner. “I come from a typical working-class family where little was said about politics. I'm aware that my work tends towards a certain 'social realism', but I try to remain as apolitical as possible for as long as I can.” But some titles might suggest otherwise - We just want to see the world, You wanted to be free on a Monday morning - where others are more descriptive: Tugboat at midnight or Your boat is coming in. There's a sense of wonder without illusion, a “heroisation” without idealization. The work is hard, it breaks bodies and marks faces, but federates thanks to a solidarity inherent to the environment. We're all one on the docks.

If Joren Van Acker's approach can be compared with that of other late 19th-century artists who depicted the world of work and industrialization - such as Henri Gervex, Jules Adler, Steinlein, Gaston Prunier or Maximilien Luce - he is closer to a young Van Gogh, who shared the daily life of miners, workers, peasants and weavers in the Borinage region of Mons. He is more inclined to weave a filiation with Constantin Meunier, one of his favorite artists, who “also depicted the inhabitants of the Borinage and lived amidst the poverty he depicted, regardless of political reasons.” In fact, we could apply Meunier's words to Joren's work, when he describes the Belgian industrial world he witnesses and speaks of its “tragic, fierce beauty”. He lets us cast off for a journey that seems timeless, with contours as blurred as his drawings, to leave room for the imaginary.

- Stéphanie Pioda, Art historian and art critic