Author: Nina lashermes

ÉTÉ FLOTTANT

LiFang

08.11.2025 – 20.12.2025

-

Aux sources n°10, 2019, Oil on canvas, 130 x 195 cm

-

Eaux dormantes n°10, 2010, Oil on canvas, 97 x 130 cm

-

Aux sources n°17, 2023, Oil on canvas, 114 x 162 cm

-

Somewhere n°10, 2025, Oil on canvas, 130 x 195 cm

-

Somewhere n°7, 2025, Oil on canvas, 97 x 130 cm

-

-

-

-

-

Since arriving in France at the dawn of the new millennium, after training in painting at the Nanjing Academy of Fine Arts, LiFang (born in 1968) has developed a body of work in which the gaze is blurred in order to be better recomposed, attentive to that fragile moment when the figure unravels without disappearing entirely. Large juxtaposed areas of flat color, modulated according to variations in light, structure her compositions. Color emerges from juxtapositions, superimpositions, and outcroppings, creating an optical depth that slowly absorbs the captive eye.

In some ways, this patient work of fragmentation evokes the accelerated flow of our era, a world saturated with images where presence fades as it is exposed.

His recent paintings depict scenes of sharing and fulfillment, bodies of bathers exposed to the transparency of daylight, captured on the beach, at the water’s edge, whose iridescent reflections retain the diffuse warmth of summer. His oils oscillate between lightness and gravity, between sharp contours and trembling surfaces. What matters is not so much representation as perception, this way of inhabiting the world through the gaze, of feeling it alive before it fades away. In this interval between appearance and erasure, LiFang explores the very duration of the visible, a space where clarity becomes memory, where painting, through successive afterimages, remembers.

Far from any demonstrative virtuosity, the artist engages in painting that is imbued with quest and experience, attentive to his own inner self, a painting that does not seek to reproduce reality, but to capture its movement, its fleeting brilliance, its density. Bathed in light, half-blurred faces and silhouettes hark back to the founding hours of modernity, when figuration and abstraction were explored in the same continuity of vision.

Both expansive and rhythmic, the pictorial gesture combines the rigor of drawing with the freedom of an airy, lively touch, carried by a subtly tangy, colorful vitality. For the removal of representations, or at least their conversion into apparitions, supports an interweaving of subtle associations forged around reminiscences, thus bringing about an imaginary fabric shared by all: a feeling of lightness and freedom, redeployed into infinity, dissolved into immensity. LiFang thus conjures up a generic, almost limbic memory, generating images that seem to spring from memory alone. It is a suspended moment, both intimate and shared, that we are given the opportunity to prolong—so that the summery, floating freshness of wonder may linger, if only for a moment.

- Maud de la Forterie,

journalist and art historian

LE SIFFLEMENT DU GEAI

Cedric Le Corf

17.09.2025 – 30.10.2025

-

Entre chien et loup II, 2025, Oil on canvas, 97 x 70 cm

-

Torpeur II, 2025, Oil on canvas, 97 x 70 cm

-

Entre chien et loup III, 2025, Oil on canvas, 97 x 70 cm

-

La chute, 2025, Oil on canvas, 195 x 150 cm

-

Le sifflement du geai, 2025, Oil on canvas, 195 x 155 cm

-

Torpeur I, 2025, Oil on canvas, 140 x 119 cm

-

Exhibition’s view, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

Inspired by his German roots, the Black Forest of his childhood, and the Baroque painting he spent so much time studying in Madrid, Cedric Le Corf is now giving shape to a dialogue he began several years ago with the landscape genre—not as a motif, but as a space to be entered, traversed, and fully experienced. From his home in Brittany, the artist explores the porous zone between the appearance of animals and their pictorial dissolution, where representation fragments to give way to an embodied sensation. What the canvas reveals is less a figure than a moving, pulsating presence, lurking in the strata of a material where oil becomes territory and the line becomes a threshold. It is there, in this interstice between figuration and abstraction, between muted violence and sylvan gentleness, that a more immediate, almost organic perception emerges. Dogs, deer, sometimes a paw, a flank, an ear, or antlers appear on the surface of the paintings. Sometimes only a trace, an animal flash, as if torn from movement. The eye believes it recognizes an identifiable scene, almost cynegetic, but it is rather the vision of a watchman, a fragmentary, lateral perception that manifests itself and echoes the figure of the jay, that bird-watcher of the forests. Here, the gaze does not aim to capture, but rather to perceive. And to paint is to become one with the unseen.

Nothing imposes itself, everything insinuates itself. Forms intertwine, recede, and ultimately dissolve in an exercise in camouflage. Something of Matisse emerges in this way of interweaving flat areas of color, in this sensuality of color conceived as layered material. Acid greens, soft and iridescent pinks, sometimes more muted shades, coming from the shadows—the palette is marked by the cycle of the seasons: nothing asserts itself and everything blends in among the foliage, branches, and other greenery.

A mutual absorption is at work and, as if through a pronounced symbiosis, the alert animal world becomes an integral part of the forest. Sandstone sculptures extend this reflection on interconnection. While porcelain once found its place at the heart of the wood, it is now these animal fragments that are integrated into the very flesh of these sculpted landscapes. And in the depths of the forest, it is a relationship of attention that Cedric Le Corf seeks to capture. It is a way of being there, intensely, without ever interrupting the momentum of life.

- Maud de la Forterie,

journalist and art critic

CREUSER

Bastien Vittori

17.09.2025 – 30.10.2025

-

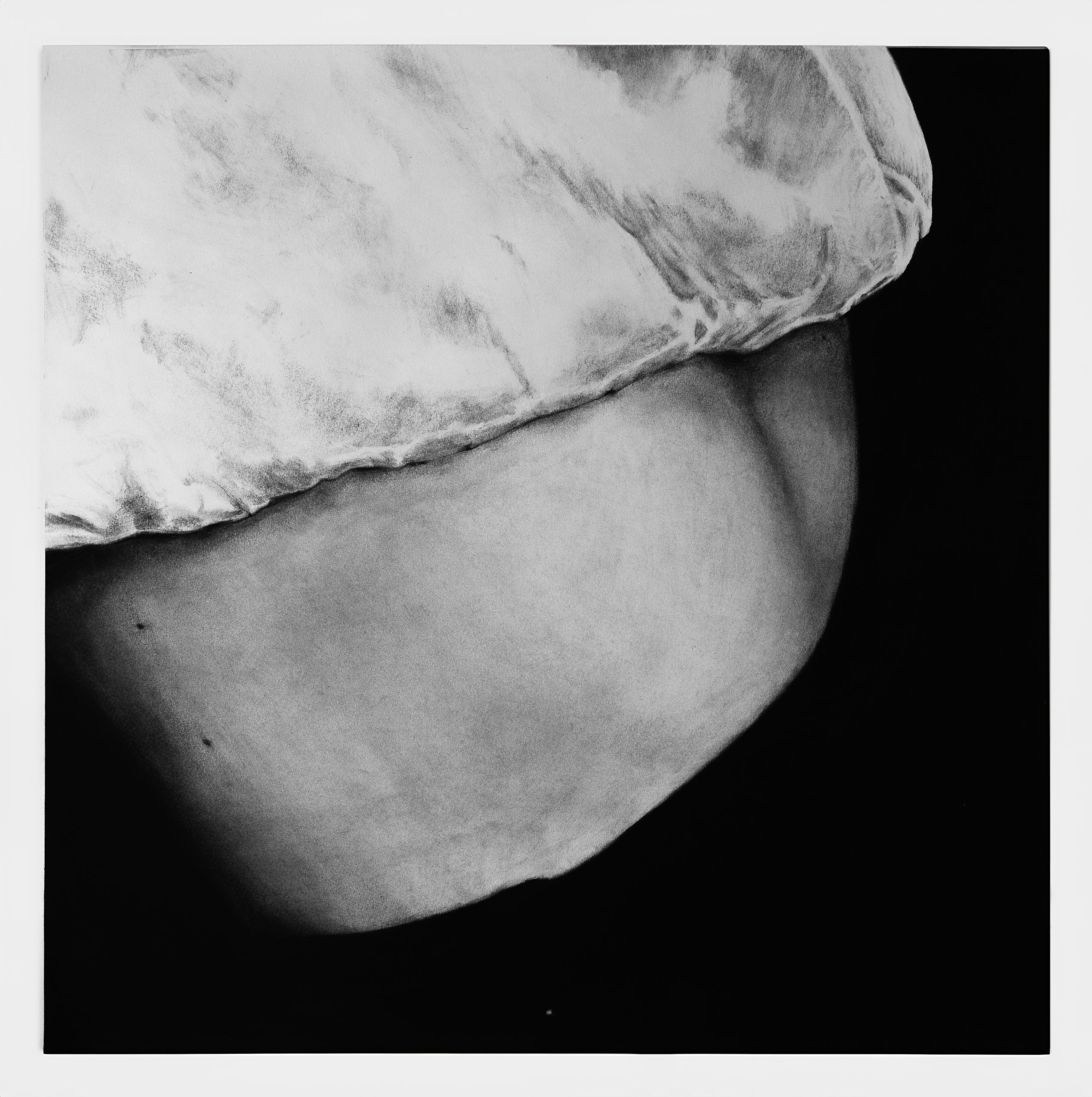

Ventre, 2025, Charcoal on paper, 100 x 100 cm

-

Vague (detail), 2023, Charcoal on paper, 200 x 150 cm

-

Hangar, 2025, Charcoal on paper, 184 x 150 cm

-

Exhibition’s view, at the Atelier, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, at the Atelier, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, at the Atelier, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, at the Atelier, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, at the Atelier, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

-

Exhibition’s view, at the Atelier, 2025 | © Aurea Calcavecchia

For Bastien Vittori, drawing is a way of exploring an image, a process for understanding what he has seen, what caught his eye during his travels, whether in a city, the countryside, a forest, or by the sea. He lets himself be carried away by a landscape until he is struck by a view of a field, by light streaming through a shed or turning into shadow, by a ray of sunshine catching on garbage bags or dancing on a rough sea. There is no hierarchy between subjects—only the poetic dimension counts—and the artist is opposed to any idea of series. The realm of possibilities is so vast that he refuses to draw the same subject twice, to lock himself into a systematic approach. Ideally, each drawing is a new subject, a new opportunity to approach a motif from a different angle. His approach reflects a way of engaging with reality through the body, matter, and touch. It is an affirmation of a point of view, of the positioning of the gaze. Or, if we take a slightly higher perspective, it raises the question of man’s place in the universe.

Through its distance from reality and the intention behind it, it transports us into the realm of the imagination. “The fundamental term that corresponds to imagination is not image, but imaginary. The value of an image is measured by the extent of its imaginary aura,” wrote Gaston Bachelard, an author whom Bastien Vittori often quotes. “Working from photography, I explore the interweaving of forms that I encounter every day: the transparency and shimmer of leaves, the mottled appearance of tree trunks, the silk of a garment. Everything coexists, intertwines, interlocks, touches. Drawing with charcoal means digging into shapes and their surfaces, digging by rubbing the page.” Although his starting point is photography, he never falls into photorealism. He keeps the overall composition, which allows him to free himself from the subject in a way, and really starts to look and call on his imagination. He draws his line on the paper, erases it, and starts again tirelessly, caught in a back-and-forth game of opposites between hiding and revealing, erasing and revealing, filling the surface and leaving empty spaces. The whites contrast with the blacks or blend into them. It is this accumulation that gives substance to his condensed charcoal drawings, close to the blacks of engravings. Very matte, very warm. “With this medium, you move more than you erase. I put my material on the sheet, then I move it, which ultimately creates movement through the accumulation of gestures.”

- Stéphanie Pioda, art historian