There is the body that is modeled, kneaded, triturated, excavated, dissected. It is transformed to the extreme with a certain fascination bestowed upon it. Between the palms of Olivier de Sagazan, matter takes life and is incarnated in unconscious doubles. Clay creatures are birthed and earth emerges through the images of the mythological beings, extirpating themselves with grand effort from the chtonian depths. Moving with clumsiness and dignity, they are an uneasy reflection of our deep, primitive nature; a throbbing, heart-rending echo that we have spent millennia repressing. Born of the earth, yet still partly stuck in it, they remind us that our bodies are made of the same vital matrix. This is "world flesh," an idea conceptualized by Merleau-Ponty who envisaged the universe as a whole through a sensitive and fundamental correlation of the elements. De Sagazan never ceases to explore this primordial ontology in an ever more intense, ever more intimate desire to pierce the secrets of life.

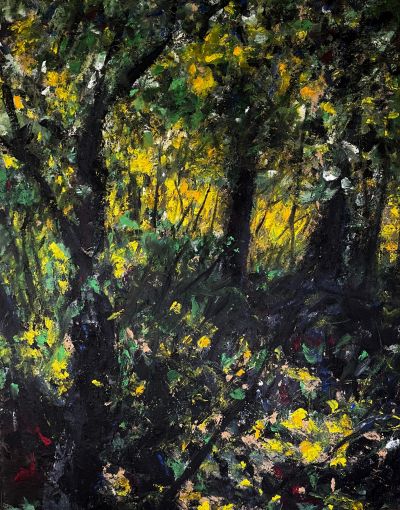

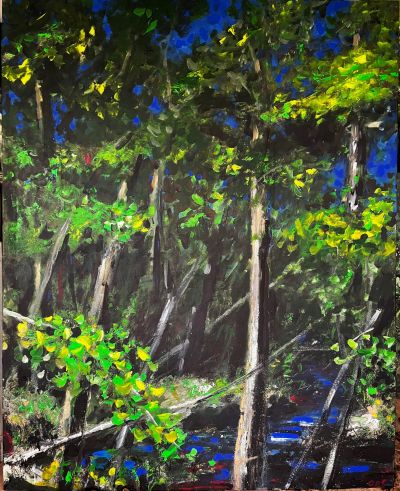

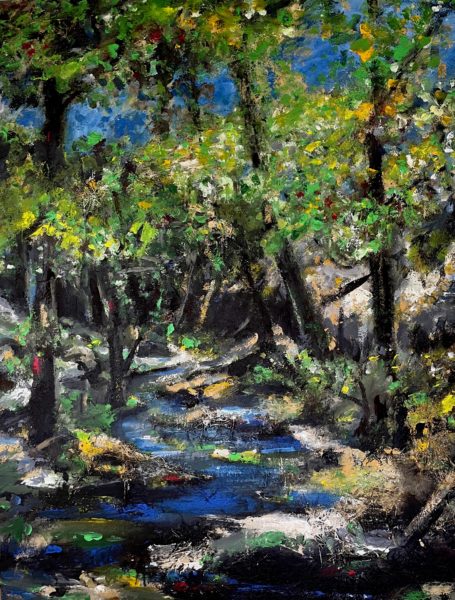

Now, the artist attacks the landscape felt as a body, yet he has removed the human figure. "For me, a painting or a sculpture is always an organism. It is a question of bringing life to it," he expresses. Facing the canvas, the artist creates more than he paints. His hands knead the clay and, this time, he has mixed it with grass, glue, and acrylic. Composite material that will never solidify, but could be sown. His body moves in front of crusty materials whose germinations stretch out in dazzling undergrowth. With large gestures from top to bottom, without any prior idea, he enhances it with bright colors, making the plants grow towards the light in a spontaneous, irrepressible impulse of elevation and depth. The texture becomes denser, materialist, welcoming reliefs and transcending any idea of representation. The painting here is not an image: it is breathing and has become "flesh." Their naturalistic textures enhanced with expressionist colors inevitably brings to mind Anselm Kiefer's dramatic fields of straw, mud, coal, and lead. Bright yellow, dreamy blue, acid green, a mysterious red… With De Sagazan, however, the landscape is anything but symbolic, it is the energy of nature whose magical body extends our own. The artist also sees self portraits in them, like a transfiguration of his conscious being within earth. He claims deep commitment in imagining a new alliance between man and nature: a nature that he has wrongly forgotten, to the point of disincarnating from it. Painting and sculpture would perhaps be the only gestures capable of making us feel this physical, biological link that unites our flesh to the world in an unfathomable sensitivity.

- Julie Chaizemartin, Art Critic